Issue 10: The resolution of memories

"Lossy compression is the class of data compression methods that uses inexact approximations and partial data discarding to represent the content."

Dearest reader,

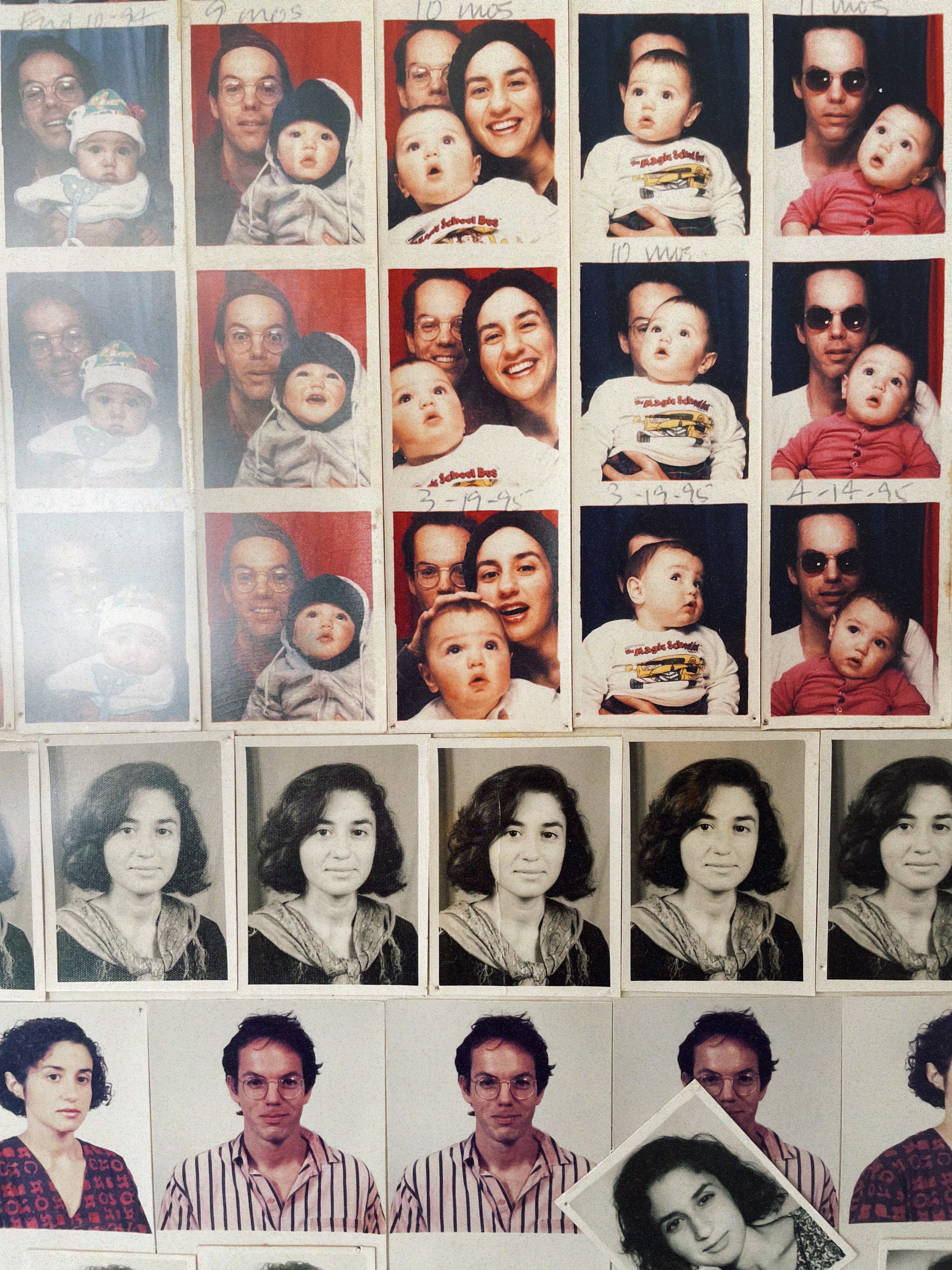

I hope this message finds you in a spirit of calm and curiosity. It’s been slightly over a week since I returned to my family’s house in Minnesota. While getting situated and settled in, I’ve encountered quite a few moments of a kind of unexpected, deep, all-encompassing—nostalgia. I’ve noticed that I tend to enter these modes when I come across once-forgotten memories of a life that feels, from where I stand today, like it existed in an entirely separate time, space, or universe.

If you were to stand outside and observe me through the various windows of its front facade, you’d find me pacing around the house, picking up and inspecting objects, looking at them for a few long seconds at a time—sometimes calm, sometimes overcome with a kind of restrained restlessness. Or sadness, perhaps. (Of the amplitude-constrained category). A thought that’s recurringly struck me over the past week is how little, all things considered, I ever learned and understood about my parents. There are numerous topics which, if I had the opportunity today, I’d love to engage them in for hours, days, perhaps even years of inquisitive dialogue.

Since compiling and sharing last week’s issue with you, I took note of a gap in my understanding of my family’s history (“the timeline”) that I haven’t yet put in the effort to fill in accurately. It has to do with my family’s transition out of Dhahran. When, precisely, did it happen, and—of all the places in the world they could’ve gone and had spoken of going—why did they ultimately return to Minnesota?

Around the summer of 2013, my mom was diagnosed with cancer. I have fragmented, incredibly low-resolution memories of her pulling me aside privately in our living room (back in the “Aramco house”) to share this information with me. I also remember her possessing a deep, unwavering commitment to pursuing treatment in Dammam, the city where she completed her own medical training.

She would frequently express a kind of contempt for people who would “fly to America” when things got bad: “Look at these kings, these princes who keep telling us how great our resources are here in Saudi—and as soon as they experience even the mildest of health complications, they fly away in their private planes to America or to their villas in Europe. The hypocrisy of it.”

And for a number of months, my mom remained steadfast in her commitment to staying the course in Dammam. She was a Saudi doctor and was going to pursue treatment in the Saudi medical system.

Until, after numerous rescheduled appointments, a number of which were time-sensitive, she got a call from the person I believe was a director at the hospital she completed her residency. From what I recall, he said something along the lines of, “Come back. We’ll take care of you here.”

And so, my mother faced a kind of ethical dilemma. Was she going to remain unwavering in her stance of pursuing treatment in Dammam, or would she move to the US, and proceed with treatment there?

At some point around or during the fall of 2013, my mom decided that she would proceed with treatment in the US, at the same medical complex in Minnesota where she completed her residency. She lived in a rented house for a year, with my younger brother initially and then with both my siblings, while my father continued to work at Aramco in Dhahran.

And thus, in the fall of 2013, did the wings of the butterfly nudge us back in this particular direction.

This is all I’ve been able to compile for you in today’s sitting. I hope you’ve found some of these reflections thought-provoking or stimulating. I’ll see you again next week. ❤️

Love,

Reef